Make It A (Virtual) Reality: Knightmare

“Welcome, watchers of illusion, to the castle of confusion.” If you were a child of the eighties there is a very good chance that line will spark many memories and possibly even raise a few hairs on the back of your neck. For you see that line was the traditional welcome on the children’s television programme Knightmare.

Knightmare was a British fantasy adventure programme produced by the appropriately named Broadsword Television which broadcast on ITV from 1987 to 1994. Teams of four children took on a quest to retrieve from the dungeon a mystical artefact: the Cup, the Sword, the Shield or the Crown. Three of the team stayed with the presenters – Treguard, the Dungeon Master (played by Hugo Myatt) and his assistant – whilst the other ventured forth blindly into the dungeon equipped only with a knapsack, eye shield (in later series) and the overly large ‘Helmet of Justice’ that allowed them only to see the floor immediately below them.

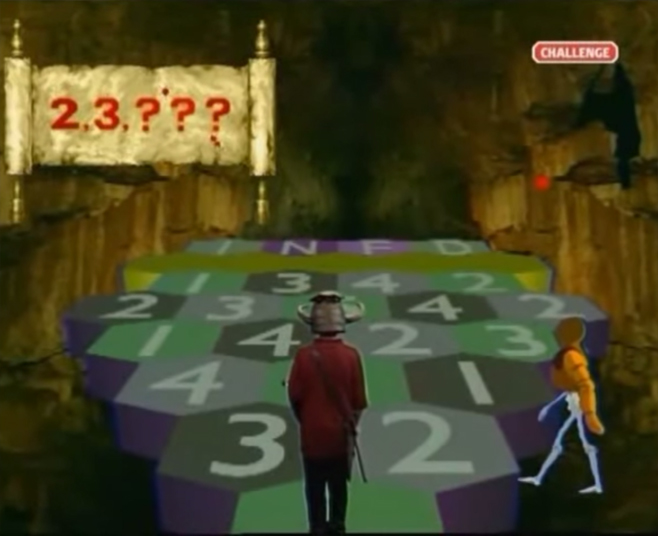

The quest took place over three levels with the advisers guiding the ‘Dungeoneer’ through a series of rooms across three levels, discovering clues, acquiring objects, interacting with dungeon inhabitants and solving puzzles often against the clock. In reality these rooms were nothing more than a series of blue screened rooms with the occasional prop or physical obstacle thrown in. What was seen on screen however via the wonders of technology was a CG created dungeon full of depth, character and peril.

Knightmare was an unusual beast for children’s television; a technical and long-running show (eight series) with a schedule that required, with the amount of set-up needed, many hours to produce a single programme. The tone of it was also a little different for many programmes of the time as well. For a start Knightmare didn’t shy away from being scary. Whilst the settings and indeed the acting was somewhat flimsy on occasions, the poor Dungeoneer was often placed in a number of apparently very dangerous situations. Spikes, fire, falling causeways, moving walkways, mechanical knights, mythical beasts acting as guardians, or a tunnel with giant saw blades flying at you were merely the tip of the iceberg.

If the team failed the Dungeoneer was deemed in nearly all cases to have died, with perhaps the most disturbing imagery being the original ‘lifeforce clock’ that was employed. The clock was one of the mechanics of the quest. In order to continue their travelling sustenance needed to be placed in the knapsack that the contestant carried. The condition of the Dungeoneer was initially shown as the face of an armoured warrior; first the helmet, skin, then bone peeled away to be left with only a pair of eyeballs which then too disappeared. The defeated Dungeoneers were brought back from the beyond by Treguard (or some other force) and reunited with their teammates before being sent on their way – ‘dismissed’ in the language of the series.

Make no mistake, whilst there were comedic elements in the series – particularly with the cast interactions and the occasional exasperated remark from Tregaurd, there was always a menace underneath waiting to pounce. To quote the Dungeon Master himself, “It’s only a game… isn’t it?”

Knightmare required both logical thought and in some cases quick thinking. Clues and key objects could potentially be missed but with a bit of luck or a clever interaction with one of the dungeon residents it was, potentially at least, possible to survive encounters that would otherwise have been a game over. Naturally though this didn’t always work and actual successful quests were rare, especially in the early series. Knightmare was tough and was prepared to pull no punches as being an actual challenge.

Knightmare along the way also created its own series mythology.

From an initial good versus evil concept, all the characters: good, bad, neutral and those somewhere in-between in an awkward grey area all grew through the interactions with the teams, becoming more rounded characters over time. Knightmare became not just about the battle between ‘The Powers That Be’ (the forces loyal to Treguard and the wizard Hordriss) and those of evil referred to, presumably as to avoid any true name, as ‘The Opposition’. Additionally it also became about the battle between technology and magic itself. In the fifth series the production team introduced Lord Fear (played to show-stealing effect by Mark Knight), the leader of The Opposition who was very specifically a techno-sorcerer. Treguard himself admitted at one point that as technology became more advanced Lord Fear would only became more powerful whilst those on the side of pure magic would not. As the series passed the stakes ramped up the success of one team would increase the frustrations on the other side to the point where The Opposition grew tired of the constant battling in dungeons and started making plans to attack Treguard and his allies directly. Teams even requiring to abandon their chosen quest half-way through in order to collect another item to save themselves from a messy end. “There’s no point having the Shield if we can’t bring it back to Knightmare Castle!” to quote one Dungeoneer.

Knightmare also has a lingering popularity, especially in the UK where it is perennially voted one of the top children’s television programmes of all time in public opinion polls. Repeats are often broadcast on the digital station Challenge and it was even brought back for a one-off as part of YouTube’s Geek Week back in 2013. The most memorable part being YouTuber Stuart Ashens (at the behest of his team) trying to mislead a potentially troublesome dungeon dweller by confidently declaring his name was, in fact, Susan. Since then a convention and even a Knightmare stage show have taken place.

So what you have with Knightmare is a brand with longevity. A dynamic fantasy experience with the potential for multiplayer interaction, a history of established characters and set-pieces and astory that works in a dynamic setting, a series history and mythology you can build on should you wish and a loyal fanbase. . It’s had video games before as well.

So with all that said, why not bring it to virtual reality (VR)?

Well to a degree they have already tried to once before. Knightmare VR was an ill-fated 2002 pilot, again using the technology of the time. It was poorly received and was subsequently not picked up. Whilst elements were similar to the original, enough of the core mechanics of Knightmare were changed to put off those fans who did see it. The technology just wasn’t ready, In a 2005 update to fans online, creator Tim Child addressed that and the inherent downside of using virtual reality – losing the reality of Knightmare.

“..principally I believe and accept that whilst a much wider gaming pattern is available via full virtual reality, the essential dynamics of the exercise may not match the original.”

And I agree that this is true, or at least it was at the time. However game and virtual reality technology have since moved on and I believe it would be a very different prospect now.

Firstly however Knightmare doesn’t have to be a television programme. There are several dungeon adventure titles already ready (or coming) for the current crop of Head Mounted Devices (HMD’s), such as Crystal Rift for instance. As such there’s nothing stopping a Knightmare-themed single player action adventure RPG experience being created. I can certainly imagine you fleeing through dwarf tunnels, carefully traversing puzzles and hiding from a menacing Frightknight, all with the sounds of a goblin horn closing in on you.

However, whilst more than plausible that doesn’t take into account the spirit of the show.

It is a team game and in much the same way any VR title should really take that approach as well. There are no VR experiences currently on the market where you are in a team situation like this, with one user as an active player and the rest tactical overseers. Yet it would be perfectly possible to do. Dungeons, items and quests could all be virtually created and visible via a headset that all parties would wear. Rooms could be generated based dynamically based on a player’s finishing position or at the end of each room the Dungeoneer could be indicated to return to the starting location. As a result the experience could take place in almost any one of the virtual reality spaces currently being developed. Advisors would have access to an interactive inventory menu, see the room and even access a version of Treguard for advice. The Dungeoneer would be the one moving, have their own more simplistic inventory and be the one to finalise all dialogue responses with in-game characters but crucially they would also have a representative display of their view restricted by the iconic helmet. Keeping the trust factor and the need for other members of the team.

You could recreate the Knightmare experience, keep it somewhat loyal to the original and take the concept to a level far beyond the restrictions initially imposed on it. It would certainly be something different.

Knightmare achieved a lot as a television show, far more than making certain the word ‘sidestep’ was in every childs lexicon. Maybe there will come a time for the show to return again, in some guise. It remains popular to this day so there is a chance. I would certainly like to see it and experience it if I could. The technology is there now. Is there a will? Is there a way? Who knows. We will just have to wait and see.

For now, until time turns again for Knightmare and any would-be Dungeoneers… Spellcasting: D-I-S-M-I-S-S.

Where am I? You’re in an article originally written by the author for VRFocus.